ESSAY

The Punjab government recently directed

the Lahore Development Authority to lay the groundwork for establishing an

independent Ravi Urban Development Authority (RUDA). Initially, the new

government body was being planned under the aegis of the LDA, however, this

plan was later scrapped. Reportedly, if the new authority is developed as an

independent government entity, then it will have its own governing body and it

will be responsible for establishing a new city along the Ravi riverfront.

Previously, the RUDA was supposed to be similar to the WASA and the Traffic

Engineering and Planning Agency. Now it will be a separate authority and the

LDA has already been directed to prepare the paperwork for the purpose.

Sustainable development

goals:

The

unsustainability of the Project from an ecological, environmental and financial

perspective argued by the Society seems to reflect a myopic view of the

ever-changing and developing world, especially in view of the ever-increasing

population of Lahore, a provincial capital. It is submitted that the Project

has been conceived in line with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the

United Nations (UN). Under the 2030 Agenda of the UN, the economic, social and

development dimensions of “sustainable development” are to be integrated in

harmony. They are to be construed as a whole and not in a fragmented manner.

One goal should not encroach upon other goals and if we examine SDG 17 (global

partnerships and cross-sector collaboration), the Project aims to accomplish a

majority of the goals listed under it by providing state-of-the-art

infrastructure and facilities, sustainable communities, job opportunities and

further healthcare and educational opportunities to its residents. Moreover,

the Society’s argument with regard to the Project’s potential detrimental

effects to the environment is also frail as the Project intends to plant

vegetation around the current barren lands of River Ravi and help with its

sanitization and treatment, which even the River Ravi Commission has, to date,

been unsuccessful with.

Sustainable

development is no doubt an evolving concept and it is noteworthy to mention

that under our domestic law the Supreme Court of Pakistan has taken a pragmatic

approach in its landmark judgment pertaining to an environmental issue

Ecosystem

The Project also claims to value the

ecosystem of River Ravi and appears committed to legally resolving any

environmental impediments for the betterment of its development. Moreover, its

concept is not only in sync with the hortatory non-binding goals of the United

Nations but is also supported by the doctrine of precedent of our Supreme

Court.

The argument that the channelization of

River Ravi is against the principles of sustainable development and ecological

sustainability has little weight at this point. Whether or not any purported

channelization of River Ravi will affect the ecology of the River is a question

to be determined by the relevant experts and consultants in the field. Their

recommendations in this regard shall be implemented in the execution of the

Project. During the Environment Impact Assessment (EIA) process, such reports

should be presented to the concerned agencies for their approval under the

Punjab Environment Protection Act 1997 (PEPA 1997).

Moreover, the Society’s argument that riverbanks

are an integral part of the river ecosystem and the hydraulics of rivers where

there is no defined edge should be maintained, is to be decided upon after

comprehensive reports by the relevant experts and consultants in the field.

During the EIA process,

such reports will be presented to the concerned agencies for their approval

under PEPA (Pakistan

Environmental Protection Act).

The reality of

River Ravi is that it is currently a “sewage nullah”, as quoted by the Prime

Minister. The benefits of implementing the project outweigh the environmental

concerns being stressed upon by the Society. Any environmental damage

apprehended at this point is pure conjecture. A proper EIA should be carried

out before the execution of the Project and all matters pertaining to the

environment and ecology of River Ravi and its surrounding topography should be

addressed through the proper medium, as per the regulatory laws of our land.

The Project is essential for the sustainable development of Punjab and will

save River Ravi from further damage.

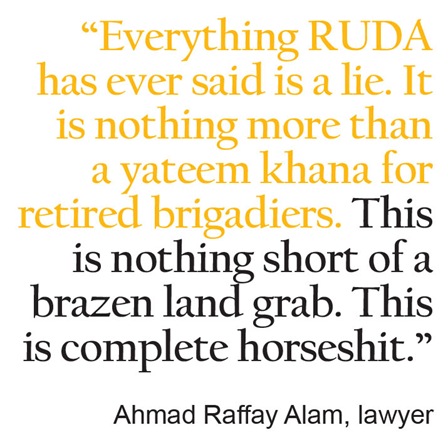

Drawbacks of

RUDA

The bulldozers

came at the crack of dawn, and they came with no warning. As they rumbled

through farmland with the watery September sun at their backs, they were

accompanied by a small army of private guards and officials from the Ravi Urban

Development Authority (RUDA). Tenants and landowners that farm the land watched

on with resignation while their crops were destroyed, and waterways

blocked.

The Ravi

Riverfront Project is many things. At its best, it is a vein, bloated,

misguided attempt that many environmentalists and hydrological experts have

called an impending ecological and social disaster. At its worst, it is an

uncaring attempt to turn the Ravi and its embankments into a playground for

real estate developers that intend to treat it as a cash-cow for at least the

next two decades

For better or

worse, it has become a bone of contention with political undertones. A pet

project of former prime minister Imran Khan, it was declared illegal and

unconstitutional by the Lahore High Court last year and has recently been given

reprieve by the Supreme Court. That verdict in addition to the PTI back in

charge in Punjab may be what is behind the latest attempt by RUDA to seize

lands that they claim they have legally acquired and which the owners of these

lands say have not been.

CONCLUSION: